|

For those of us who are old enough and were somewhat “woke” back then, the COVID-19 pandemic invokes hidden emotions that remind one of the painful early years of the AIDS crisis. There are differences, certainly, because this pandemic is directly affecting a broader demographic, but the similarities in the feelings the COVID-19 pandemic revisits are striking and haunting.

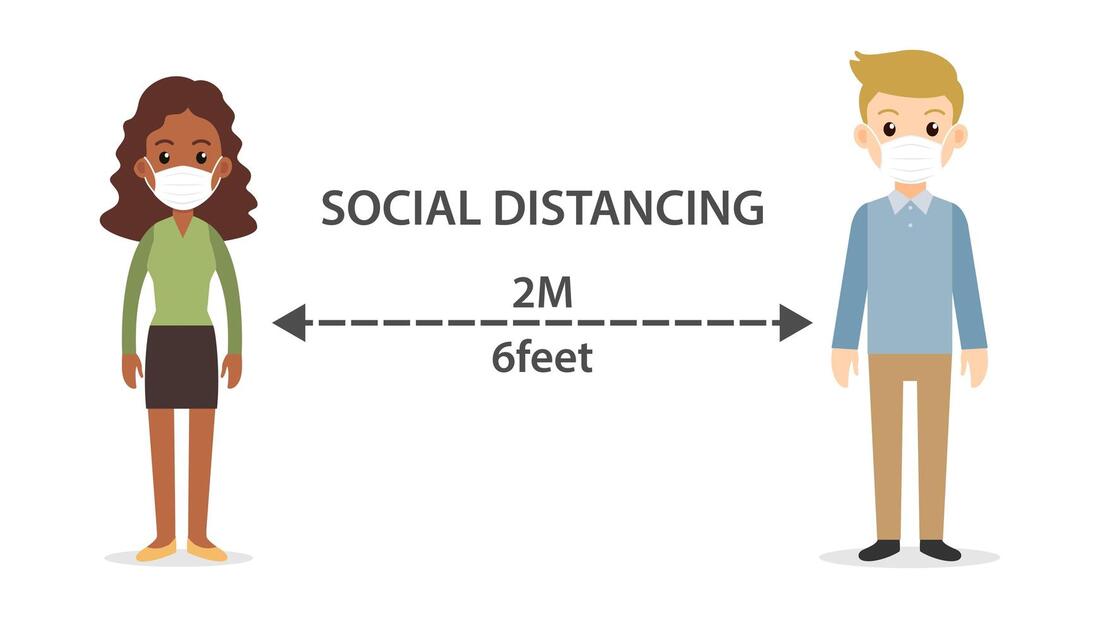

In both, American presidents who couldn’t think beyond their own egos reacted with sociopathic indifference to the disease and deaths of real human beings. Ronald Reagan will always be remembered as the president who refused to speak about, much less act to solve, HIV. Today, Donald Trump seems willing to let the rest of us go if he can just keep his approval rating up among his base, his profits flowing in, and the stock market paying its richest investors windfalls. In both, the leaders placed the blame on someone they wanted us to think of as a dangerous Other to deny the pandemic’s wider existence and, more importantly, their own personal responsibility for failing to act effectively and with a national sense of a community in crisis. Then it was put down as the “Gay Plague” and now it’s the “China Virus.” In both, leaders who could have thought in terms of how we’re all in this together mouthed the otherwise instructive words: “personal responsibility.” But they were usurping those words as a cliché to provide an excuse for government failure, a reason to do nothing in the belief that the plague would only affect other people and families, to raise guilt and shame in any victims as if to punish them further by doing so, and to downplay the systematic homophobia, racism, sexism, classism, and able-bodiedism that are major factors affecting the most devastated. Then as now, right-wing religious leaders spoke self-righteously of these pandemics as some Divine punishment upon all those that didn’t tow the sectarian line by which they made a name for themselves and money to live better than those who idolize them. Their hell-fire seemed to always have something to do with their fear of equality for LGBTQ people and their phony self-righteous claim of victimization in culture wars. In both, the science was way behind, and that was often because other things were more important in the profits-over-people game played by conservative and libertarian-type politicians. They spoke of socialism threatening the nation while predatory capitalism was destroying needed safety nets. It was Ronald Reagan who changed the rules so that hospitals could be for profit. Preparing for and treating pandemics were considered economic losers. Then, as today, there was the fear. It was a nagging, aching, dread dwelling always in the back of the mind. In most early cases, being diagnosed as HIV positive was a death sentence. Big pharma was concerned first about its bottom line and had to be forced to seek remedies - the earliest of which (such as AZT) were just as likely to kill the patients. When I told a graduate student that I had just learned about the death of a young colleague at another university who’s books already challenged entrenched religious historian’s biases, that student unhesitatingly expressed the feeling of that day: “Will there be anyone left?” Today, most who contract COVD-19, we’re told, will be fine in the long run. Yet there are few markers assuring us who won’t be okay, who’ll be left without the help they need because of short supplies, and who, as a result of maintaining a stiff upper lip should have been more cautious. We’re even watching its spread to our healthcare providers. For quite a while no one was sure what to do to prevent the spread of the virus. Those who tried were still afraid that they hadn’t done enough. Today that’s: Have I washed my hands enough or the right way? Did I touch my face too much even without being aware? Will the package from the grocery store, the clerk who rung it up, or the stocker who shelved it spread it to me? How certain can I be of the safety of packages delivered to our door? How long is the virus alive on what surfaces? One result then, as now, was a widespread, lingering situational depression. Few pointed out then that that’s what it was, but it took an emotional toll. Today, too, most of our nation is experiencing situational depression. As Yale psychology professor, Jutta Joorman put it: “It will take some time for us to see the long-term mental health effects of this situation, but it has a lot of the ingredients that can affect people’s mental health negatively in a significant way.” And then, as now, social distancing was recommended. Back then, when no one first knew whether one’s touch, breath, saliva, sweat, sneeze, or other body fluids could transmit infection, people needed to separate, use all the latex between each other they could, and fear any bodily contact. Today social distancing includes the end of all bodily contact, even a six-foot distance from others, and staying home for weeks except for running essential errands. When what we need is a connection, physical contact, being with others, and sharing face-to-face our fears and depression, this plague denies us all that. No wonder there were people who opted for connection, intimacy and touch then and now by breaking the rules and defying the depression, the odds, and the criticism of those of us who obeyed. It wasn’t safe; it wasn’t helpful, but it was somewhere human. As I remember those days, my mind returns to the couple dozen or so students who sought me out for some connection when being diagnosed as HIV positive was pretty much a death sentence. Our encounters went something like this as they appeared at my campus office. “Professor Minor? May I talk with you for a minute?” the student at the open office door would ask, often with a light knock on the door or its frame. I always kept my door open and my desk facing the door to welcome those who came. “Yes, come and sit,” I responded as I pointed him to the chair at the side of my desk, not one on the other side where my desk provided some official demarcation. Erasing the barrier was important to me. “I think it’s safe to talk to you,” was the first clue. “You’re the first person I’m telling about this.” The student was always taking, at least, his second class from me. So, he felt he knew me. I got up myself to provide a bit of privacy by pulling the door open, but not closed. “I just found out that I’m positive,” then revealed the purpose of this visit. The words, too often familiar, hang even today in my memory. They would talk about how unfair it seemed. They had thought they were taking enough precautions and had believed that their partner was. I listened and agreed: “It’s not fair. There’s nothing ‘fair’ about it.” “I don’t know how I’m going to tell my roommate (and/or my parents). I’m from a small town. I know this won’t go over well. And I’m scared.” I listened to everything else they wanted to share while my eyes teared up. I’m surprised I could hold it together. And then my student felt he needed to go. But before he left my office I said something I had never said to any students except these. I said: “Will you give me a hug?” Some of those students were well-known student leaders who never shared their secret with others on campus. But many months later it was seldom an exception to learn that “they had quit school and gone home to ‘be with their family.’” I knew that meant “in their last days.” So that office visit was also their last. I still believe those hugs were important then just as hugs are now. They were intentional. I didn’t want anyone ever to think that the first person they confided in about their place in the AIDS pandemic felt in any way that they were now too unclean for human touch. By making this connection to a professor they felt “was safe,” they had actually bestowed on me the honor of being the first person they told. So the very least I could give was the kind of hug, let’s admit, we all really need, but can’t have, today in these weeks and months of this new pandemic. P&E Robert N. Minor, Ph.D., Professor Emeritus of Religious Studies at the University of Kansas, is author of When Religion Is an Addiction; Scared Straight: Why It’s So Hard to Accept Gay People and Why It’s So Hard to Be Human; and Gay & Healthy in a Sick Society. Contact him at www.FairnessProject.org.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

P&E - After PrintHere are some of the latest articles and topics in the GLBT community. Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed